Aaron Lubrick: "Looking Beyond"

Exhibit Statement, May 2021

Exeter Gallery, 241 S. Exeter St. Baltimore MD 21202

Aaron Lubrick: Looking Beyond

May 15th – June 30th

Reception with the artist on Saturday, May 15th from 6-9pm

Aaron Lubrick is an artist who has dedicated his professional life to drawing & painting and inspiring a younger generation of artists. He has exhibited throughout the east coast and Midwest and is a member of the Perceptual Painters Group. Lubrick was instrumental in starting up an Art & Design College in Kentucky. He currently serves as an associate professor of Visual Arts in Painting and Drawing at Spalding University in Louisville, KY.

Lubrick's work is physical, emotive, and eschews virtuosity of paint handling for what he considers to be a truer bedrock of expression: color combinations and forms that reveal the artist's movements with paint. His work is often based in perception as he works on site, from memories, or from intuitive experience. During his painting process he strives to move beyond the initial image relying on impulse and strong feeling. His work celebrates the beauty of the world surrounding him, a world replete with signifiers of a boy's life in the American midwest: kids on bikes, the landscape as seen from a car window, trucks, and lazy days at the swimming hole. There is a nostalgia and at first blush, a naivety to these scenes. The artist knowingly offsets this “American apple pie” aesthetic with ominous undertones.

Children silently watching in harsh light as black smoke billows skyward. Heavy skies press down upon a bounce house during the pandemic and red skies glow like embers over an earthmover as it tears the soil.

Lubrick's work is effervescent despite an uncertain present and future. Lubrick's optimism in a time of cultural upheaval and the crushing effects of the pandemic are a case study in “near miss effect.” Both the artist's personality and his work show that a buoyancy of thought and deed serves us well. He has a direct and joyful approach to painting which is bound into each painting's surface. These works inspire and can make any non-painter desire to pick up a brush.

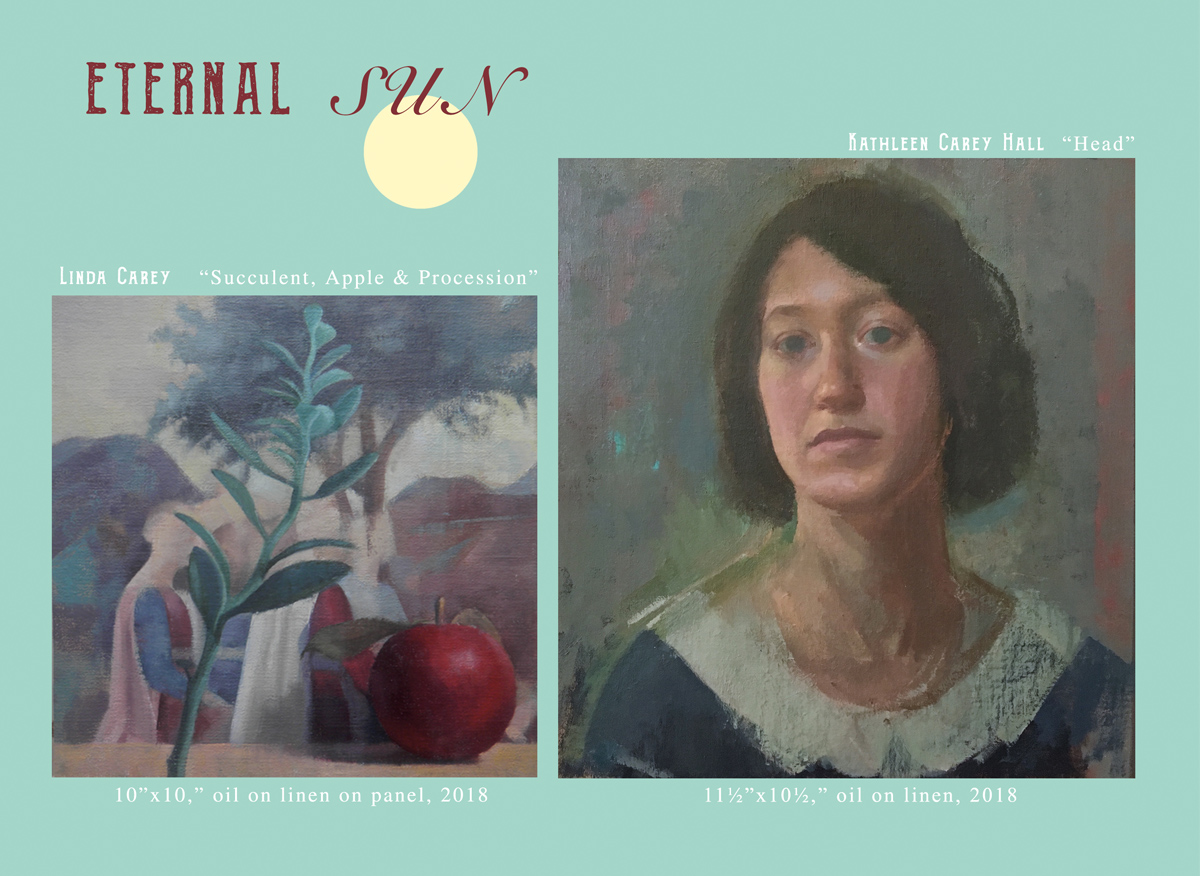

"Eternal Sun" Linda Carey and Kathleen Carey Hall

Exhibit Statement and Showcard, November 2018

Exeter's second exhibition of its second season features another Mother & Daughter duo. Linda Carey and Kathleen Carey Hall create methodically crafted paintings. The work is inspired by a sensitivity to the objects found in their immediate surroundings and an affinity for the pantheon of great Italianate art and architecture. Linda has spent several months in Italy each year since 2003 and Kathleen has visited albeit for shorter stints.

Exeter's second exhibition of its second season features another Mother & Daughter duo. Linda Carey and Kathleen Carey Hall create methodically crafted paintings. The work is inspired by a sensitivity to the objects found in their immediate surroundings and an affinity for the pantheon of great Italianate art and architecture. Linda has spent several months in Italy each year since 2003 and Kathleen has visited albeit for shorter stints.

Both artists create art from art. Each creates paintings featuring other paintings within them, and in the case of Kathleen, creates landscapes and interiors from found tree branches, collected paper scraps and the like. In this way her work is among a strong contemporary contingency of artists interested in the metaphysics of painting. Among them are Amy Bennett, David Campbell, Will Cotton, Matt Jones, Andy Karnes, Caleb Kortokrax, Sangram Majumdar, Bradley Mulligan and Kerry James Marshall; specifically, his paint by number paintings. These artists conflate images, collage, and three-dimensional constructions in the making of their painted works.

Kathleen Hall's “Landscape” shows us a bucolic landscape painting surrounded by verdant leaves. The landscape painting in this still life, indicated by the softer hues and overall blue/gray quality within its rectangle, sits high and to the left of the composition. Our view which is both cast down to the landscape painting as it lies on the table top and out across the vista in the landscape sets up the complexity. The dense vegetation surrounding the painting of the landscape is painted in an almost collage-like manner. Oddly, the image of the landscape, two steps removed becomes clearer than the vegetation printed on the table top on which the landscape painting sits. That which is more removed is more realized. Hall uses setups which evolve and as these shift the paintings shift too. The process is one of give and take and is born of a mindset that is pensive and even empathetic towards these simplest of objects. She states, “I am not so much interested in understanding my subject as I am in drawing out its strangeness” which brings to mind Francis Bacon's quotation, “The job of the artist is always to deepen the mystery.”

Linda Carey incorporates reproductions of early Italian paintings as a backdrop to the pitchers, fruit, and dried leaves assembled in her still lifes. Each is arranged and color keyed to the historic image; Giotto with crimson and piercing blue, Piero with tepid green and earthen gold. These paintings serve as votives to the preeminent influences on art and image making in the western world. Carey's paintings are meditative, and touch-to-surface is of utmost importance. It is as if we assume the role of the creative and hear the inner call and response which may be in the artist's mind while actively painting:

Should the edge crystalize here or remain barely visible?

Should the color mottle or smoothly transition?

Should this shadow become dark and cavernous or radiate an inner glow?

Carey's paintings are small chambers in which the forms echo from front to back. These reverberations in the form of arches, triangular peaks, and vertical interstices unify the works and at times baffle our reading of illusionistic space. It is in the awkward flatness or the hard to place shape that the works begin to inhabit a poetic space. These paintings push beyond their love letter origins to show us a wholly integrated scene wherein the master works as we know them dissolve and we are baffled, once more, to find the light and color achievable in the painted image.

Both Linda Carey and Kathleen Hall arrive at their art by working from life. These artists, working under the same sun which illuminated the studios of the great artists of the Renaissance, hold onto a traditional ethic and yet are showing us a vision that is unique and timely. As we move forward in uncertain times the sun continues to rise and art continues to be made in the context of art that came before. May it always be so.

"Things Forgotten"

Gallery Francoise for BMoreArt, April 2015

Two young painters mount an ambitious exhibition at Galerie Francoise. “Things Forgotten” features the work of artists Ryan Schroeder and Andrew Karnes. Both painters attended MICA for undergraduate school and Schroeder is currently completing an MFA at New York Academy of Art ('15) while Karnes went on to earn his MFA at BU's College of Fine Arts. Both painters reveal a common core in silent pensive interiors. Yet key differences emerge between these artists in treatment of surface, the interior motif, and the emotional base of the works.

Schroeder's six large canvases command attention and their expansiveness is unimpeded by the grand fifteen foot interior walls of Galerie Francoise. Five smaller paintings by Schroeder line the front wall of the gallery with a small tondo nested in the center of the far wall. His paintings of an abandoned duck farming town in Riverhead, New York and abandoned buildings in both Shanghai and Leipzig reveal many scrutinized moments of detail but remain openly painted.

Distressed timbers lean against walls that allow light to leak through. Large metal scraps and debris litter the floors of these cold empty rooms. All of the large paintings, except one, are predominantly matte and their lack of luster coupled with paint scrubbed into the fibers of the burlap leaves an eerie impression. The surfaces are scumbled and stained with strategically located elements of thick impasto.

Schroeder is a mixologist using all manner of elements as additives to his paint including marble dust, dryer lint, human hair and scraps found on site. On his relatively sheer surfaces an occasional mass of paint and material, reminiscent of the globs of goo that sometimes build up in shower drains, adds to a feeling of malaise. These masses amplify the juxtaposition that exists between the quality of illusion and the attention to surface that Schroeder obsessively fights to balance even if, at times, the masses feel a bit too stuck on. Schroeder's small paintings contain an incredible amount of muscularity and decisiveness. A tilting composition, “Interior 3,” depicts a wall, floor, and distant doorway that manifest itself through the tooling of dense paint. The strength of this painting matches that of the large works.

Andrew Karnes exhibits seven smallish works and two large paintings immediately to the right as you enter the gallery. His paintings rely on a decidedly tonal structure, but within that structure colors emanate. “The Meeting” is perhaps his strongest painting in the exhibition and it becomes apparent that this ‘gray' painting is really a somewhat globular flow of subtle colors.

Golden grays ooze into blue gray and then a violet as sections of the floor and the metal folding chairs overlap and dissolve into one another. His surfaces are somewhat thickly painted, semi-gloss, and sensual. Karnes's subjects of interior environments, primarily of his studio and perhaps a college classroom, reveal pensive intimate views that have a universal quality but under his hand become deeply personal.

Each painter ultimately seems to be concerned with opposite poles of the interior working world. Schroeder portrays a blue collar world that seems to be fading into memory. I'm reminded of this by my daily commute past the now closed Bethlehem Steel Plant which used to employ over thirty-thousand workers and is currently being dismantled in hunks round the clock as I type these words. The other world is that of the knowledge worker and, in Karnes's case, this is the not quite white-collar world of the classroom and cubicle interior.

Schroeder overwhelms us with austere cold places and the force of the paintings and the latent emotionalism creates a robust tension. His industrial interiors have become outmoded. They are the inner bowels of the leviathan that have produced our objects of consumption. Karnes' interiors invite us in and enable us to trace the simple forms of everyday objects as he did by patiently responding to the soft light spilling from fluorescent lamps and windows just beyond the picture plane. The force of these paintings can easily be missed due to their non-confrontational stance. Karnes's interiors reveal a pensive and poetic space that rewards a viewer's slow read.

This exhibition, while presenting the work of two significant young talents, is also a celebration of Galerie Francoise, a venue which has steadfastly served up contemporary art to Baltimore viewers for nearly 25 years. The gallery's director, Mary Jo Gordon, opened her gallery in 1988 with a series of outdoors sculpture exhibitions at Greenspring Station. In 2000 the gallery moved to their current location in Woodberry, although it has moved to a much grander space within the building in recent years. To see the space, meet the director, and the artists highlighted in “Things Forgotten” stay tuned for a discussion at the gallery which is tentatively set for mid-May.

Fragments of Fort Howard

Sabbatical project by Matt Klos, September 2014

“It was like finding the ruins to an ancient city in the jungle,” he said. “You wouldn't believe that in 50 years a place could go back to nature like that.”

On an unseasonably warm Saturday morning in late winter 2011 I packed a large panel and my paints into my truck and drove 3.7 miles to Fort Howard. I had stumbled upon this 47 acre parcel of federal property situated at the end of the Sparrows Point peninsula during the occasional drive or jog along a surprisingly rural stretch of road. Since the road that leads from my home to Fort Howard leads in the opposite direction of work, shopping, friends, and family it was never on my way but remained on my mind. The majesty and decay of these places left an indelible impression on my mind.

On an unseasonably warm Saturday morning in late winter 2011 I packed a large panel and my paints into my truck and drove 3.7 miles to Fort Howard. I had stumbled upon this 47 acre parcel of federal property situated at the end of the Sparrows Point peninsula during the occasional drive or jog along a surprisingly rural stretch of road. Since the road that leads from my home to Fort Howard leads in the opposite direction of work, shopping, friends, and family it was never on my way but remained on my mind. The majesty and decay of these places left an indelible impression on my mind.

The painting I began that morning in 2011 remains unfinished like nearly a dozen other paintings I've begun at the Fort Howard site. Although unfinished artworks are understood as a natural occupational byproduct for artists it may seem strange to some. Why go through all the trouble to begin something and not bring it through to fruition? During my time working at Fort Howard there were a number of reasons why I would abort work on a painting. Occasionally it was due to a significant shift in the season or due to a visual equation that I couldn't quite sort out. In these cases the paintings are waiting for the seasons to roll around again and for a new solution to be dreamed up. More often, however, my interest in the initial idea, the thesis of the painting, waned over time. In these cases the paintings merely fizzled out and have been sanded down and painted over.

In summer 2013 I embarked on my sabbatical project at Fort Howard by preparing dozens of 2' and 4' square painting surfaces. My full time pursuit during the summer and fall of that year was focused on the completion of a series of paintings documenting the structures situated on the Fort Howard grounds. Fort Howard, although largely unoccupied still maintains an outpatient clinic which is open on weekdays and is watched round the clock by security officers to prevent trespassing and vandalism. As a painter and professor of visual art I keep a consistent studio practice and my professional time is split between teaching and personal work. Before my sabbatical it had been nearly seven years since I had been able to pursue studio work for full time. By my estimation a project of this scope would have taken several years without the generous support of the college and the granting of a sabbatical which allowed me to work full time in the studio once again. I am grateful to Dean Dan Symancyk, Vice President Trish Casey-Whiteman (both of whom have recently retired), and Anne Arundel Community College's Board of Trustees for their efforts in making my sabbatical request a reality.

Leading up to this project I saw two deeply moving exhibitions which helped shape some of my goals. "Richard Diebenkorn: The Ocean Park Series” retrospective at the Corcoran Gallery and "De Kooning: A Retrospective” at MoMA. Both exhibitions confronted the viewer with an impressive sense of scale and various series of works that seemed to be directed by rigid self-imposed rules or restraints. Additionally both artists showed great courage by not “buttoning up” or editing expressive aberrations that fell across the surfaces of paintings. It seems that these aberrations serve to balance the more ordered and deliberate marks on the paintings' surfaces netting a gestalt effect that is both emotional and cerebral.

On a sweltering night in August 2011, just two weeks after completing Fort Howard #7, I heard fire engine sirens for the better part of two hours. It wasn't until two days later when I arrived at Fort Howard and saw the yellow police tape that I realized where the fire trucks had been heading that evening. The white house pictured in Fort Howard, #7 had burned to the ground scorching the giant sycamore tree that grew in front of the house and leaving a pile of rubble and three pillars of brick where the chimneys stood. I set up and began to paint the wreckage but was asked to leave shortly after beginning to work since a police investigation was underway. During the short time I worked that day I could hear the Ospreys scream and sense their agitation as they flew over the burned wreckage which had held their nest. After the fire access to the premises has been strictly limited and for non-veterans a revocable license is needed to visit the Fort Howard site.

While working at Fort Howard I had the pleasure of meeting and hearing from a number of interesting folks. Some belong to families that have lived in the Fort Howard area for generations and some have lived in the military homes within Fort Howard's grounds. As an example, in early August 2014, an elderly gentleman, who was driving through with his daughter stopped to chat as I was painting the theatre building. He said that when he was a young boy his family didn't have much money and he would come and sneak into the theatre. He said that the soldiers knew he was there but they didn't mind. He also mentioned that there was a “colored cook and a white cook” who he would make a point to visit. They were good to him and always gave him a bite to eat. This story and dozens of others were conveyed to me during the making of the project.

Painting onsite and in the elements had its challenges. Lugging large panels, a studio easel, folding table, 3' palette, and two boxes of paints to the worksites required on average an hour of setup and teardown per session. Some days were uncomfortably hot, interrupted by torrential rain, or painting was abandoned due to the cold and frustration of trying to work in winter gloves. Sometimes when momentum was gained on a particular sunny day painting the clouds would roll in for several days and interrupt my flow. More than once large panels would catch a sudden gust of wind and topple. It was not always possible to find a shady spot in which to stand while also getting a desired view of my subject. As November and December came the days shortened significantly making work on sustained paintings ever more challenging. In spite of all of these things, and indeed, because of these things ideas came to me that certainly wouldn't have come if I had not been working from life. Working from life, or perceptually painting, requires grafting imagery together and the resultant image is less about one moment in time but rather a collection of many moments in time. The rewards of painting onsite far outweigh the numerous inefficiencies, false starts, discomforts, and frustrations. I had been working on Fort Howard, #6 for about a week in early October. All the while the sky had been an airy and unchanging cerulean blue. Then one morning a patch of magnificent alto cumulonimbus clouds drifted in place and remained for the better part of the day. I spent nearly five hours, an entire painting session, that afternoon reworking the sky which I feel has greatly enhanced the overall effect of the painting. I want to point out that the initial sky was working but it simply didn't work nearly as well. If I hadn't been there to experience the phenomenon of that day in that particular place I would have missed a critical opportunity.

An account of the Fort Howard facility which was submitted to the National Register of Historic Places in 1979 accompanies this paper. Dates of historic record and some facts regarding these structures can be found within.